People from all over the world, in different cultures and religions, have practiced some form of sacrifice. Whether it was to please a god, seek forgiveness, or keep some kind of cosmic balance, it’s something humanity has been doing for thousands of years. But when we look at Jesus’ death on the cross, we see something that really stands out from the rest.

What makes it so different? Well, there are three big reasons: it was intentional, it was for everyone, and it was once and for all.

One of the most powerful things about Jesus’ death is that He wasn’t forced into it. In John 10:17-18, He says, “I lay down my life… No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord.” That’s huge. He didn’t get caught in the wrong place at the wrong time or die just for the sake of being a hero. He chose to die for a purpose.

Now, other traditions talk about noble deaths too. Think of Socrates, the Greek philosopher who drank poison rather than run away from what he believed in (Plato, Apology). That’s admirable, but it was more about personal honor. Similarly, in Hinduism, animal sacrifices in Vedic rituals (Rigveda, 10.91) aim to sustain cosmic order, not to personally bridge a gap between humanity and the divine. Jesus’ death, on the other hand, was meant to bring people back to God. He wasn’t just a martyr, He was both the priest and the sacrifice.

Another thing that makes Jesus’ sacrifice unique is that it wasn’t limited to just one group of people. Hebrews 10:10 says, “We have been made holy through the sacrifice of the body of Jesus Christ once for all.” That means it wasn’t just for the Jews, or for a certain tribe, or people from a certain time, it was for all of us.

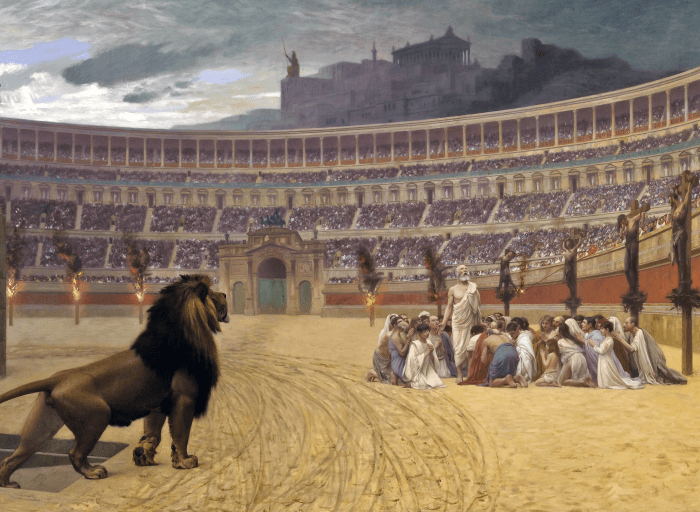

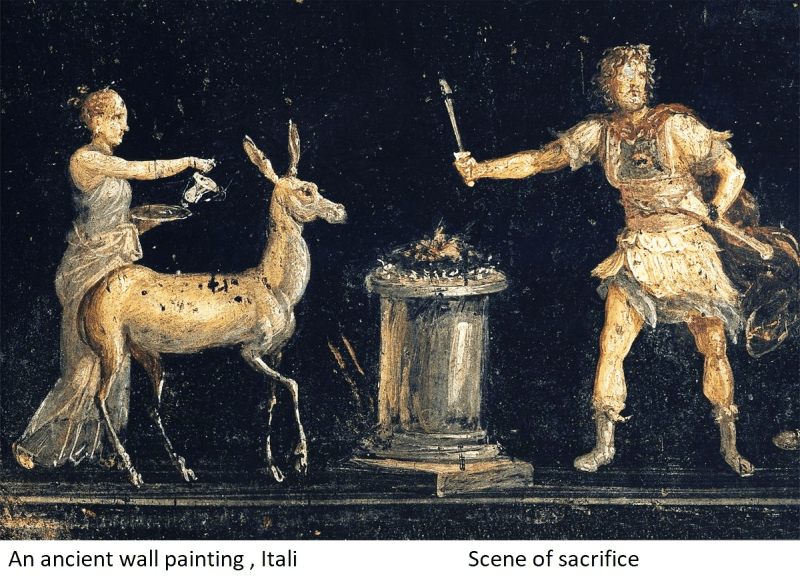

Other religions had sacrifices too, but they were often done just for a specific community or to honor a local god. For example, the ancient Israelites had the Day of Atonement once a year, and only the high priest could do it, for Israel. And in some cultures like the Aztecs, sacrifices were made to specific gods in hopes of things like rain or victory in battle (Florentine Codex, Book 2). But Jesus’ sacrifice reached across time, culture, and race. It was global.

Most ancient sacrifices had to be repeated year after year, or even more often. It was never-ending. But Jesus’ death was different. Hebrews 9:26 says He “appeared once for all… to do away with sin by the sacrifice of himself.” That means it was complete. Done. No do-overs needed.

This stands in stark contrast to the cyclical sacrifices of ancient pagan religions, such as Rome’s suovetaurilia (Livy, History of Rome, 1.7), or even Buddhism’s karmic atonements, which rely on ongoing personal effort rather than a singular, completed act.

When you step back and look at the big picture, Jesus’ sacrifice isn’t just a church teaching, it’s something totally unique in all of history. Religious scholar Mircea Eliade, who studied sacrifice across many cultures, found sacrifice everywhere, but nothing quite like what Jesus did.

He wasn’t just another teacher or martyr. He was God in the flesh, choosing to give His life, for everyone, forever. And that’s what makes His sacrifice so different, and so deeply personal for each of us.

Agape,