The Manuscript Evidence for the Bible’s Preservation

The Bible’s preservation across millennia stands as a testament to its enduring reliability, backed by an unmatched trove of manuscript evidence. With over 5,800 Greek New Testament manuscripts and more than 19,000 in other languages, the Bible dwarfs all other ancient texts in sheer volume. This vast collection, paired with its textual consistency, builds a logical and compelling case that today’s Scriptures faithfully echo their original form.

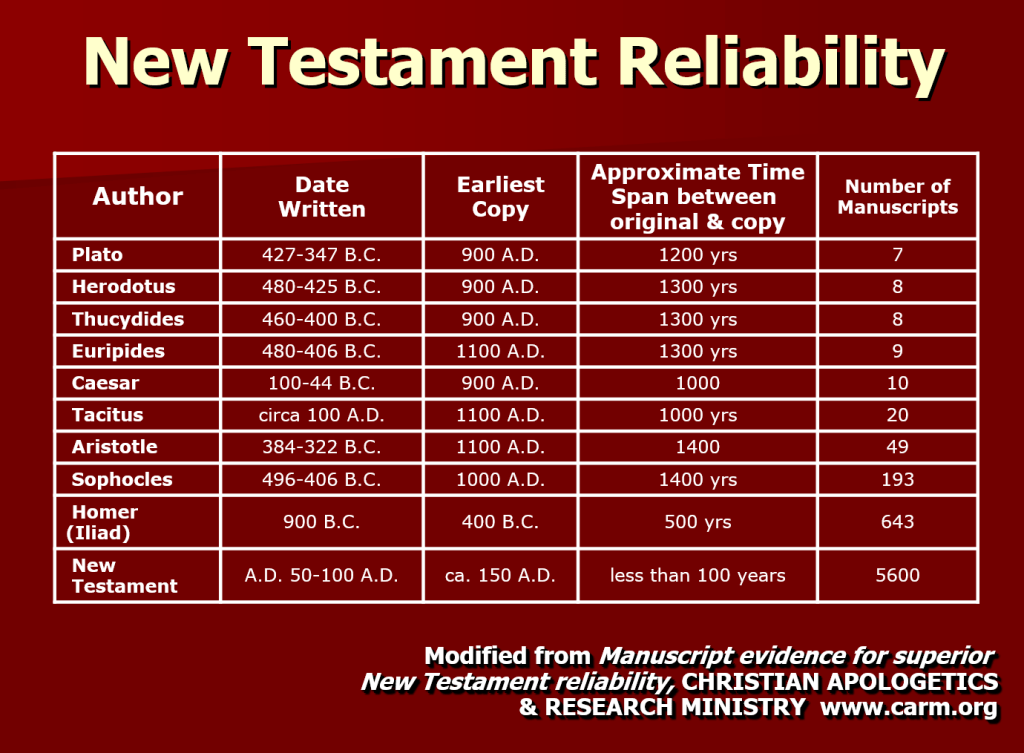

Take the New Testament: The Rylands Papyrus (P52), dated to around AD 125, preserves John 18:31-33, penned just decades after the Gospel’s origin. Contrast this with Caesar’s Gallic Wars, where the earliest copies lag 900 years behind the original, yet face little skepticism. The Bible’s early manuscripts, hundreds before AD 300, shrink the window for distortion. F.F. Bruce, in The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (1943), asserts this abundance yields a text 99.5% accurate, with variants largely trivial (e.g., spelling in John 1:1).

For the Old Testament, the Dead Sea Scrolls, like the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa^a) from 125 BC, showcase precision. Isaiah 7:14, foretelling a virgin birth, aligns almost perfectly with the 10th-century Masoretic Text across 66 chapters. Minor shifts, like phrasing in Isaiah 40:3, leave meaning intact. Daniel B. Wallace’s Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament (2011) praises the scribes’ meticulousness, reflecting their obedience to Deuteronomy 4:2’s command against altering God’s Word.

This consistency holds across key doctrines. Christ’s divinity (John 1:14), God’s covenant (Genesis 17:7), and salvation through faith and baptism (Acts 2:38, preserved in Codex Vaticanus, 4th century AD) remain unshaken. In Acts 2:38, Peter’s call to “repent and be baptized… for the remission of your sins” mirrors countless manuscripts, showing no doctrinal drift despite centuries of copying. The volume of texts enables rigorous comparison, a privilege rare among ancient works like Homer’s Iliad (643 copies).

Such preservation stems from deliberate effort, not chance. Jewish scribes counted letters per line, while early Christians, under persecution, shared copies widely—Paul even instructed in 1 Thessalonians 5:27, “I charge you by the Lord that this letter be read to all the brethren,” fostering circulation among congregations. This dedication ensured texts endured, as urged in 2 Timothy 2:15 to handle truth diligently. The Codex Sinaiticus (4th century AD) and later Byzantine manuscripts align closely, bridging continents and eras.

Skeptics may doubt miracles, but the manuscript evidence refutes claims of textual unreliability. From desert caves to medieval scriptoriums, the Bible’s words have weathered time, emerging intact. In a sea of ancient literature, Scripture stands as a rock—its message preserved not by chance, but by a legacy of care that echoes its own call to endure.

Agape

Sources:

Bruce, F.F. The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? Eerdmans, 1943.

Wallace, Daniel B. Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament. Kregel Academic, 2011.